Meaning actually springs forth from gaps and flaws and mistakes.

Jay Dolmage, Disability Rhetoric, 2014

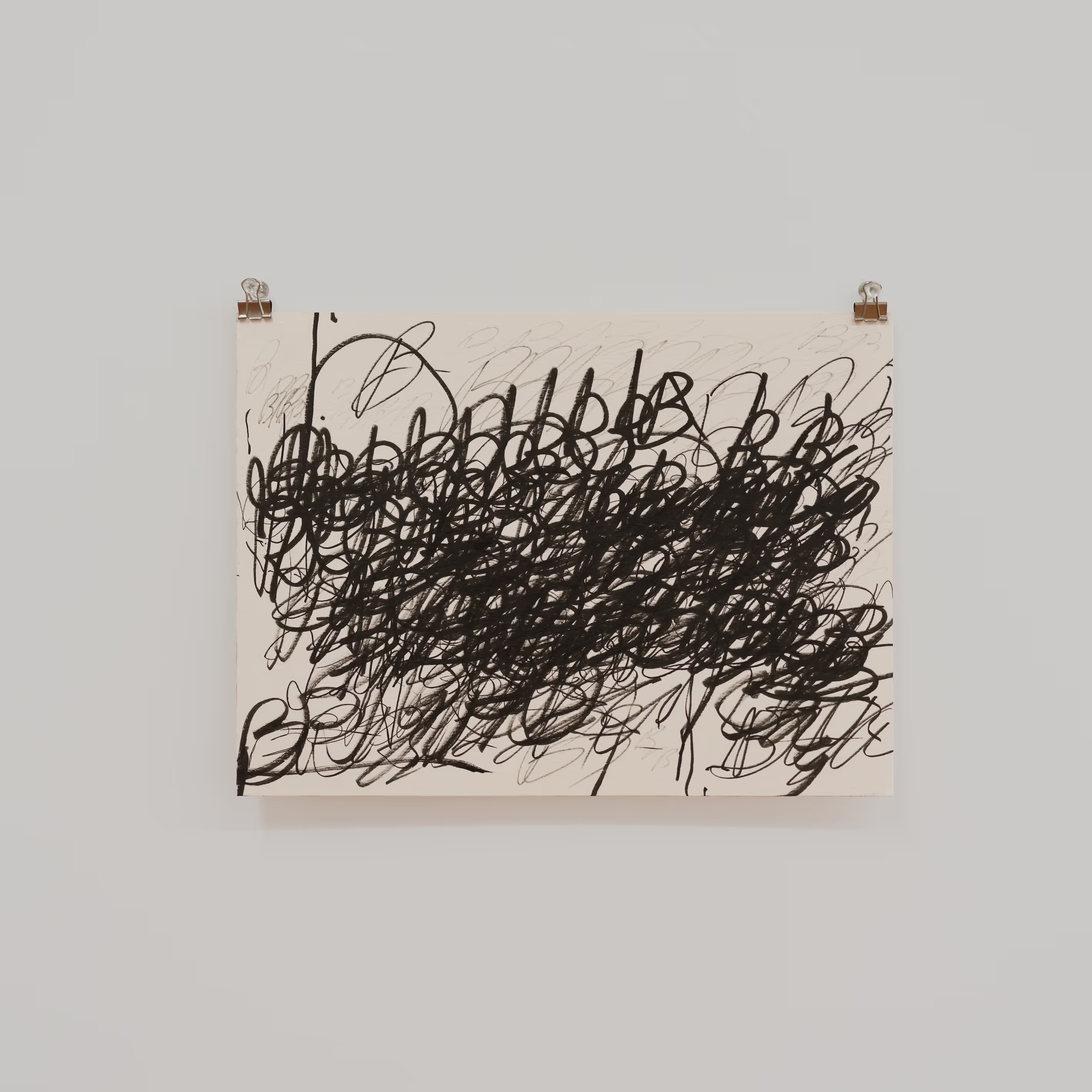

The Engine of Meaning

What is a stutter? The answer to this question will depend on how we understand communication. If we turn to biomedicine, we enter the familiar domain of compulsory fluency where stuttering is defined as a lack of fluency:

A fluency disorder is an interruption in the flow of speaking characterized by atypical rate, rhythm, and disfluencies (e.g., repetitions of sounds, syllables, words, and phrases; sound prolongations; and blocks), which may also be accompanied by excessive tension, speaking avoidance, struggle behaviors, and secondary mannerisms.

American-Speech-Language Hearing Association, Fluency Disorders, 1993

From this perspective, the goal of speech is accident-free communication. No mishaps nor misunderstandings allowed. Stutterers become a faulty piece of machinery that requires intervention to be repaired. Repetitions, prolongations, blocks, and related behaviors are “malfunctions” in language that turn into social disasters. The “fix” becomes the job of expert “mechanics” who restore the broken parts to their intended function of sending messages without delay or error.

We suggest that biomedicine misunderstands communication: Accidents are not simply errors but an everyday and even necessary part of human communication. This makes stuttering more interesting than a mere disorder. Inspired by voices like JJJJJerome Ellis, we can ask: “What is fluency? A lack of stuttering?”

In other words, what if stuttering reveals something important that fluency lacks? What if fluency (sending messages without detour or error) isn’t the true measure of meaningful communication? Misspeaking a single word can change the meaning of an entire sentence. For an air-traffic controller, this could be a disastrous accident, but in everyday life such mistakes are normal and often spark humor and new directions of conversation. Accidents are the engine of meaning and creativity. From this position, perhaps the problem of stuttering isn’t “broken parts” so much as a social obsession with preventing any and all accidents that would interrupt the predictable flow of thought and communication.

A Catalogue of Dysfluent Accidents

Stutterers are familiar with communication accidents: saying things we didn’t quite mean to say, being misheard, or watching our repetitions pile up as onlookers stare. Communicating by accident is so familiar to make it worth reimagining definitions of stuttering. We can move away from the pathological framework of disorders, which casts them as breakdowns that reside within people, to explore the idea of dysfluent accidents—unpredictable events that happen between people. As a start, here is a brief catalogue:

(Adapted from St. Pierre 2023)

- The blurt. Stutterers punctuate our speech with tics and so-called “fillers.” We sometimes grimace and groan in the act of speech. We sometimes find ourselves in the midst of speaking sounds, words, or phrases we did not fully intend. We say things by accident. In the moment of stuttering, we often feel moved by forces larger than ourselves.

- The misfire. Stuttering includes what biomedicine calls prolongation and repetition. Stuttering may extend the opening sounds of a word (e.g., aaaaaaaagree or bo-bo-bo-book), which ableist listening interprets as misfired attempts that everyone can silently agree to ignore.

- The stall. A repetition can seem to serve no purpose, like repeating most of a sentence multiple times to get a “running start” on the difficult final word that was long ago guessed by our impatient listener. Or, in a hard stall, the voice suddenly and unexpectedly runs dry. A word stops in our throat—an accident has happened somewhere—and everyone must wait for traffic to clear.

- Crossed wires. A regular experience for stutterers, crossed wires describes the state of “talking past each other” that might begin when one party mishears the other and then feeds the misunderstanding back into the conversation.

- The detour. Biomedicine prefers the term avoidance to describe the strategy stutterers employ when we sense an oncoming sound over which we expect to trip. I might, for example, begin to say “I agree” but change course, swerving around a potential misfire to substitute on the fly: “I do not know.”

- The cut-off. Here, anxious listeners rush to the scene of the accident and interrupt by finishing the dysfluent speaker’s sentence in an effort to restore fluency.

- The gridlock. Stuttering ferociously at the front of a queue, for example, halts the flow of information, people, and commerce; it stalls a lane of traffic and tempts impatient honks in the form of tapped toes and glances as everyone waits for an unknown time until information, and thus money, will once again flow free.

In each of these scenes, the accident is not caused by an individual breakdown (like the brain of the stutterer) but is a complex interaction between speakers, listeners, and other forces. In particular, the need for high speed and total clarity in communication helps turn the surprising parts of stuttering into something potentially dangerous.

Communicating by Accident

When well-laid plans go astray, unintended and unexpected things happen. Being caught in a communication accident is vulnerable and can be dangerous. But it is also true that what seems like a mistake is often, instead, a variation—a swerve from predictability—that creates something new. As the painter Bob Ross would famously say: “We don’t make mistakes; we make happy accidents.” Consider the happy accidents that continue to feed many scientific and cultural breakthroughs like X-rays, penicillin, or the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Or we might consider Surrealism, glitch art, and the creative misunderstandings that punctuate everyday conversation.

When the goal of communication is to follow the forest path and deliver a prepackaged message, stutterers are just unhappy accidents waiting to happen. We swerve off course and interrupt the predictable flow of speech, often causing delays and sparking misunderstandings. But in the clearing, we can approach accidents differently. Misunderstandings, big and small, are expected if communication is an ongoing act of creating meaning together. In the clearing where accidents flourish, no one is master of the situation. Instead, we learn to navigate both happy and unhappy accidents together—this is how all meaning gets made.

When I stutter, I’m watching with curiosity the way my listener reacts—confused for an instant—and thinking about how delicate all our conversations are, how sensitive to any pause or interruption.

Emma Alpern, “Why Stutter More?”, 2019

In this way, dysfluent accidents are moments that reveal the delicate and cocreated nature of all speech. What seems like a breakdown in communication is actually a heightened moment when ableist rules of communication stop working and speakers and listeners must instead rely on each other. So-called breakdowns are thus sites for new meanings and new ways of relating to emerge, invitations to reorient how we speak and listen.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- In what ways does society frame people who stutter as “broken parts” that get blamed for communication accidents? If we understand stutterers as more than “broken parts,” what else might be the cause of communication accidents?

- In what ways do communication accidents help us to establish deeper, more intentional meaning together?

- Which of the listed accidents (blurt, misfire, stall, crossed wires, detour, cut-off, gridlock) have you experienced? What were these experiences like, and how does dysfluency studies reframe these experiences?

- What are some happy accidents made by stuttering? Think about specific experiences where stuttering has brought joy.

- How might destigmatizing these dysfluent accidents help us respond differently in everyday communication?