Idealized Speech

Before going further, let us consider a broad question: What is fluency? As a starting point, fluency is defined as speech that flows off the tongue smoothly, predictably, and without effort. The word fluent once referred to a stream or current of water, and it still means nimble and quick movement. Fluent speech is encountered like a swift brook: It jumps to the ear freely and leaves a pleasing impression. A fluent flow of words is neither stagnant nor turbulent; neither held back nor forced out; neither fixed nor chaotic. At the same time, “speaking a language fluently” implies a mastery of a language, dialects, cultural knowledge, and nonverbal cues. Fluency shows mastery of speech. It is predictably smooth—without accident or error. Fluency is ideal speech.

While the word fluency has been in use only for a few centuries, the notion of ideal speech has existed since ancient times. For instance, the ancient Greeks contrasted their own “civilized” speech with what they perceived as the repetitive babbling of non-Greeks, whom they called “barbarous” or barbarians. The word barbarian itself mimics the seemingly dysfluent sounds (“bar-bar-bar”) that the Greeks associated with ethnic outsiders. People who could “merely babble” were not considered full human beings. The practice of marginalizing people who sound different from a more powerful group has survived throughout history and continues into the present. Ideal speech still functions as a password into the human community, and dysfluency (combined with other forms of nonideal speech marked by race, class, gender, and sexuality) continues to make people outsiders.

Pleasing the Listener

Of course, each and every person stumbles over their words on a regular basis. Fluent speech is impossible to maintain at all times. While fluency seems like an effortless task, it requires time and energy, even for nondisabled folk. This makes sense: Systems that aim to make people normal emphasize the need to achieve a social standard without visible effort. Fluency is “good sounding” speech that pleases the listener. It must thus appear to roll off the tongue (and into the ear) without effort. To maintain the myth of ideal speech, individuals and society as a whole must keep this effort hidden.

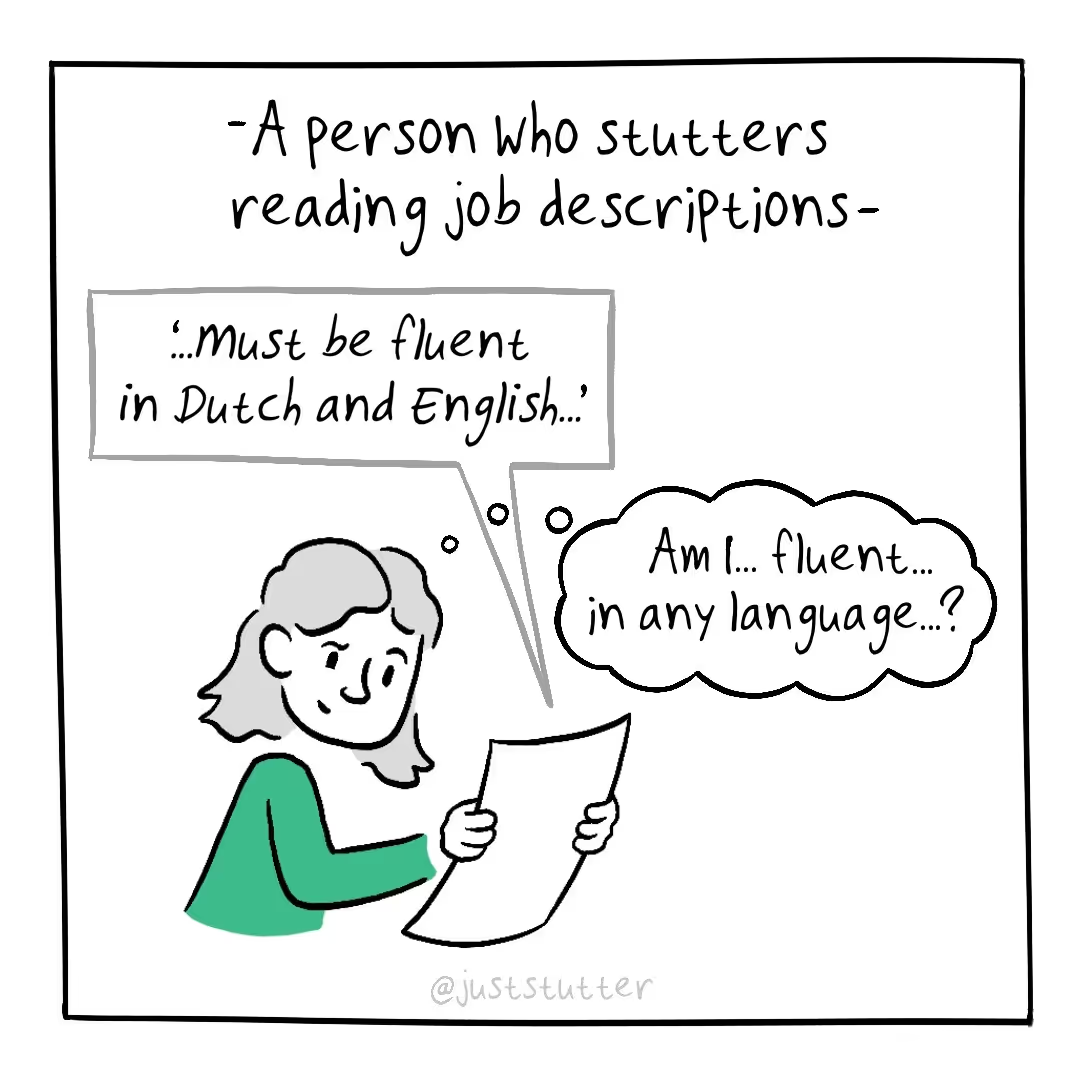

The term compulsory fluency refers to the expectation that all speakers—if they want to be heard and taken seriously—will be fluent. From the perspective of the listener, compulsory fluency is the expectation that people will hear only predictable and effortless speech in the world. When non-stutterers make small pauses and repetitions in speech, ears that expect fluency “fill in the gaps” and pretend nothing happened. But when the effort in speech becomes too great to ignore, compulsory fluency pushes dysfluent speech out of the common world.

A society in which everyone communicated and moved with ease, and became more alike, would be culturally and even spiritually barren.

Barry Yeoman, “Stammer Time”, 2019

A fluent speaker is often rewarded for meeting the listener’s expectation of fluency, while a dysfluent speaker can be penalized for failing to meet that expectation. Research shows that in everyday interactions, fluent speakers are often assumed to be more competent, confident, and intelligent than dysfluent speakers. In society, fluent speech leads to better treatment by listeners than dysfluent speech. Dysfluent speech is often dismissed in frustration or viewed with suspicion: Spit it out! What are they hiding? Why are they nervous? The suspicion grows much stronger for those whose voices are already stereotyped as “dangerous” or “untrustworthy” in society because of race, gender, or sexuality.

The reverence for fluent voices is created, in large part, by hearing them repeated thousands of times in film, television, radio, poetry, and prose (in other words, culture) until it feels true in our gut. Trusted news anchors deliver polished reports; clear and impassioned speeches sway juries; the radio host with free-flowing speech seems authentic. Meanwhile, the collective fear of stuttering voices is built and maintained in a similar way: linking dysfluency with danger and deceit again and again. Think of the villain in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, “poor stuttering professor Quirrell”; Edward Norton as a killer who fakes a stutter in Primal Fear; or Colin Firth in A King’s Speech, where the stutter becomes a danger to the empire itself.

Stereotypes and biases such as these slip unnoticed into many areas of life, such that fluent folk and dysfluent folk end up being perceived and treated differently in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. For example, we invite our readers to reflect on this list:

FLUENT PRIVILEGE CHECKLIST

- I can pause or work through a word without others finishing it for me.

- When I introduce myself and say my name I can trust that no-one is going to smirk, laugh, or make an unpleasant joke about my speech.

- My competence is judged by what I say, not on the smoothness of my speech.

- I can speak spontaneously without needing to rehearse words or worry about being misunderstood.

- I can take part in a classroom discussion, oral presentation, or interview and be pretty sure that I will not be penalized for the way I talk.

- I can apply for a job requiring excellent communication without wondering whether the way I speak will be seen to meet the criteria.

- I am not more likely to be incarcerated because of how I speak.

- Voice-recognition systems (for example, virtual assistants, voice to text, or automated customer service) usually understand me without error or frustration.

- I can take phone calls without being disconnected, misunderstood, or asked to repeat myself excessively.

- My official testimony, complaints, or requests are not called into question because of how I speak.

- I do not worry that my speech will influence perceptions of my fitness to parent.

- Media representations of people who speak like me are common and not framed as comedic relief or “inspirational” figures.

- I can easily find characters, public figures, and role models in films or television who sound like me without it being the central focus of their identity.

- I am not randomly tasked with “fixing” my speech by peers or medical professionals.

- I don’t consider the energy required to speak before engaging in a conversation.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- How does the expectation of fluency combine with expectations around gender, race, sexuality, or class to create the shape of an “ideal” person? What does that person sound like? How does dysfluency disrupt it?

- Review the “Fluent Privilege Checklist.” What are some of the different ways in which you might experience fluent privilege? How have you unconsciously re-enforced the norms that produce fluent privilege?

- Where have you seen stuttering represented in film or TV, and what does stuttering communicate about those characters? How do these representations reinforce negative stereotypes and feed into fluent privilege?

- How does being fluent give people social and institutional advantages over those who speak dysfluently? What can fluent speakers do to shift that power?

- How can you work to dismantle compulsory fluency in your own life? How can these practices be implemented on community and institutional levels?