Introduction

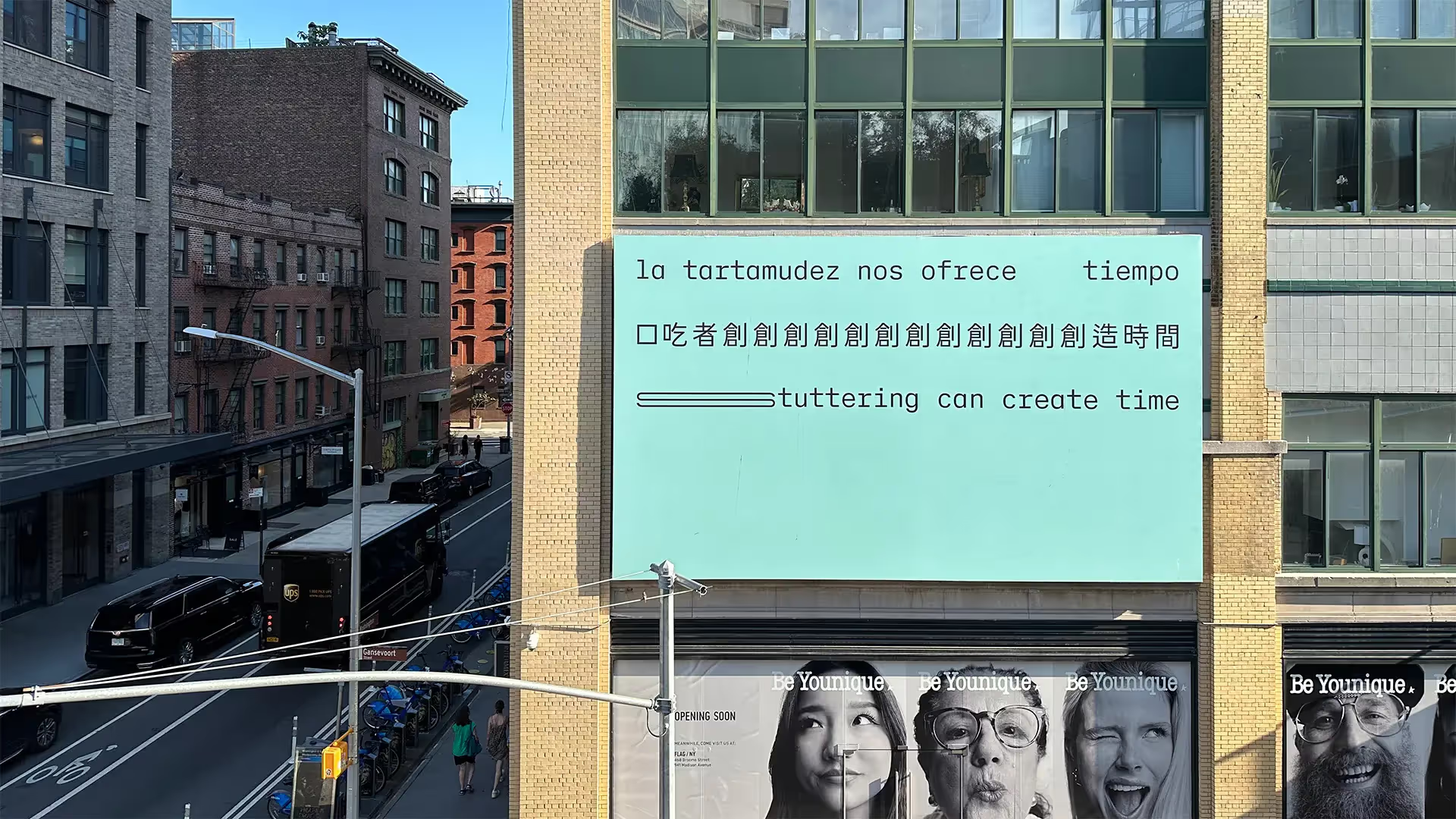

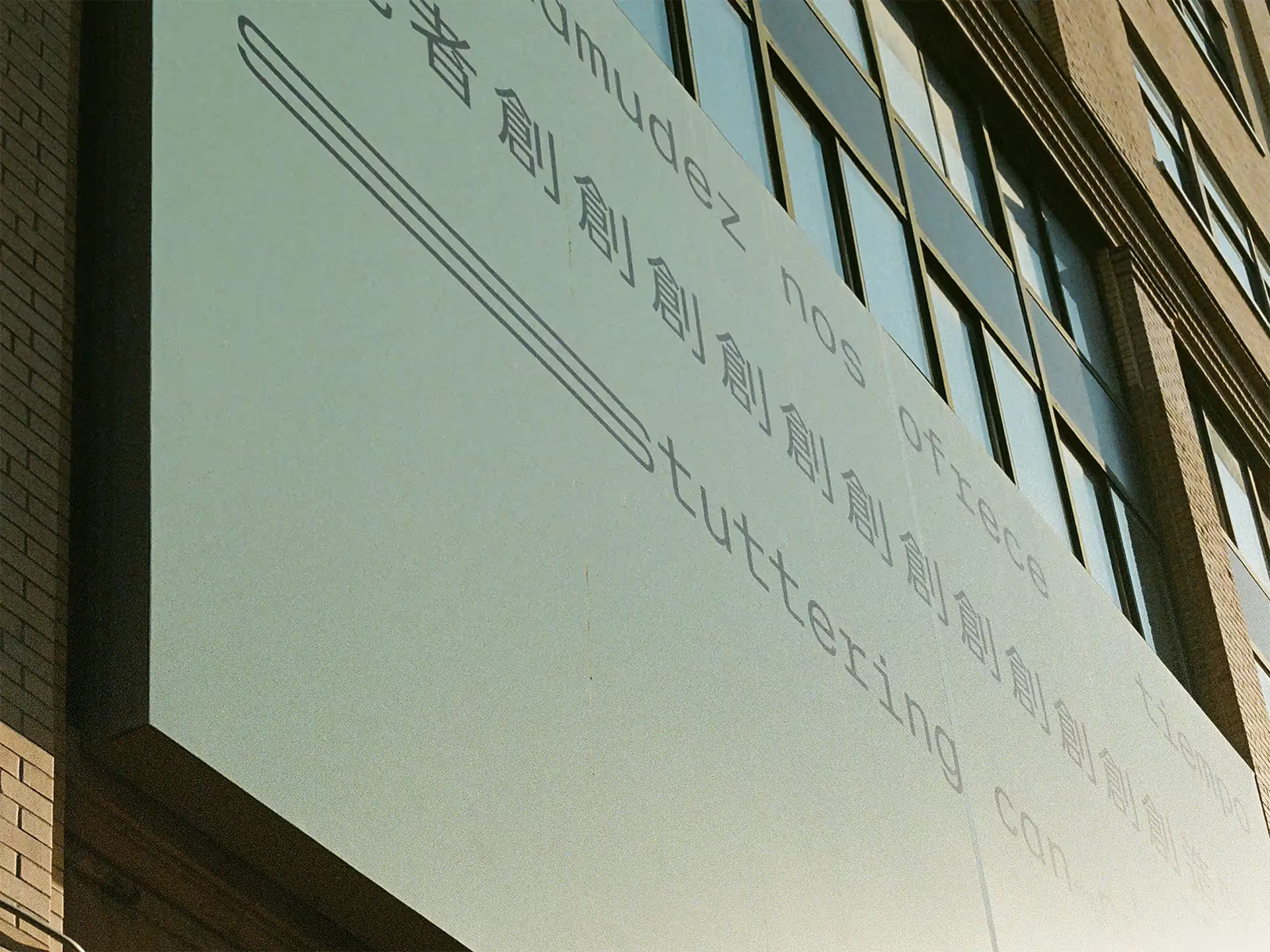

In 2024, a group called People Who Stutter Create made a piece of public artwork in New York City to challenge people’s ideas about stuttering. On a busy street, they displayed a large billboard that held a single phrase repeated in three languages: “Stuttering can create time.” Against a light blue background, the phrase is printed using a custom font designed by one of the artists (Conor Foran) that makes the words stretch and repeat in the space.

“Stuttering can create time” is a bold statement because stutterers often feel the opposite. We feel time as a pressing weight. We feel time slipping away. We feel out of sync in conversations. We miss the timing of jokes or automated phone prompts. Employers tell us we waste valuable time. To understand the transformative meaning of the billboard, we need to start by explaining the difference between two types of time: inner time and outer time. As will become clear, stutterers are already familiar with this distinction.

Keeping Time

Since long before the invention of the clock, humans have kept time. We mark its passage using day/night cycles, lunar cycles, seasonal changes, and mundane activities like boiling water at a certain time each morning. Ancient civilizations made sundials and star charts to measure the passage of time and divide it into hours, days, seasons, and years. We continue to understand time through hunger and fatigue, fertility and pregnancy, aging, and how long it takes the body to heal a wound or speak a sentence.

Of course, stutterers know that the time it takes to speak is anything but simple. When we stutter, our inner sense of time often clashes with outer time. A one-second block in speech might make us feel like time has stopped entirely. Inner time refers to our personal flow of experience—the way minutes can race by when chatting with a friend or crawl when waiting for them. Outer time refers to time that can be measured, divided, organized, and controlled.

Sharing Time

If left to ourselves, each of us would float through our day on a slightly different current of time. This would be nice for daydreaming but less so for activities that require coordination. For example, making music. In a band, the sound of a drumbeat and a bass line synchronize its members—and the audience—in a shared experience of time. Listening to the band, we are swept into a feeling of time happening together. In the same way, caught in a good conversation, speaker and listener merge into a moment of time that unfolds for them simultaneously. When you and I share time, it forms a “we.” If either you or I step out of a shared time, the “we” falls apart.

The problem is that compulsory fluency lays down an inflexible beat that forces stutterers outside of shared time. Compulsory fluency is an order of time that rules social lives. Our speech gets pinched between the time it takes our bodies to stutter and the external demand to speak quickly and efficiently. It is in the moments when we are cast out of shared time that we feel time getting away from us.

To use JJJJJerome Ellis’s distinction between stuttering “on-time” and “in-time” when we try to speak “on-time,” we always arrive late. When we stutter on-time, we stutter according to the rules of the clock, rules that have always been tied to making money. Here, in a capitalist society, time is a commodity (where time equals money). Here, only efficiency can create time. Stuttering can only destroy it.

But if we stutter “in-time,” something happens. Time can gather and pool. Stuttering frees time from the clock’s endless march and allows us to experience a deeper and richer sense of what time is. Rather than keeping pace, the goal is to “stutter in-time” and fully inhabit both time and our stuttering.

I often know in advance if I’m going to stutter. The word becomes like a bud, as if the stutter has yet to bloom. Depending on the syllable, sometimes when that word arises, I can use my breath and mouth muscles to suppress the stutter. Other times, I try to practice letting the stutters bloom as fully as they want to. This takes focus because I have so many ingrained habits of trying everything I can do to avoid stuttering. One answer to what being “in-time” is to me, is to bloom in full stutter.

JJJJJerome Ellis, “Music of Liberation”, 2025

When unhooked from the beat of fluency, stuttering can even create time, allowing us to relate to one another (and our own voices) in new and surprising ways.

My stuttering might cause my fast walking co-worker to slow her pace or maybe even stop walking to engage with me. The forgettable exchange is now replaced by something unique. The co-worker is forced to connect with me.

Chris Constantino, “Stutter Naked”, 2019

A block on a word does not stop time but harbours it. Involuntary repetitions do not empty time but fill it. Time becomes a habitat in which stutterers can live when time doesn’t rush away, but when past and future are allowed to collect and dwell together. Stuttering can do this work of creating new shared rhythms, new ways of sharing time.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- For stutterers, when does time feel the most oppressive? What can be done in these situations to lighten the burden of time?

- Can you think of moments in your own life when time felt slowed down or expanded? How do you relate to the idea of “clock time” contrasted by “dysfluent time”?

- What can stuttering teach us about alternative ways of experiencing and sharing time?

- If dysfluency was allowed to shape our social rhythms and the tempo of our conversations, what effect might that have on the world around us?

- JJJJJerome says “the stutter is an instrument”, framing a stutter as something generative and valuable. Does this quote resonate with you? Why or why not?