Communication as Shared

It might sound like a cruel joke: “How many people does it take to stutter?” But behind that question lies a real issue. While the standard biomedical answer tends to be just one, we suggest it always takes at least two people to stutter.

Consider a thought experiment: If a voice stutters in a forest with nobody there to hear it, did stuttering really occur? Many people would assume it did, because only one person would be making the stuttering sounds. Yet we suggest this misses what stuttering truly is. After all, stuttering is part of a communication process that needs both speaker and listener.

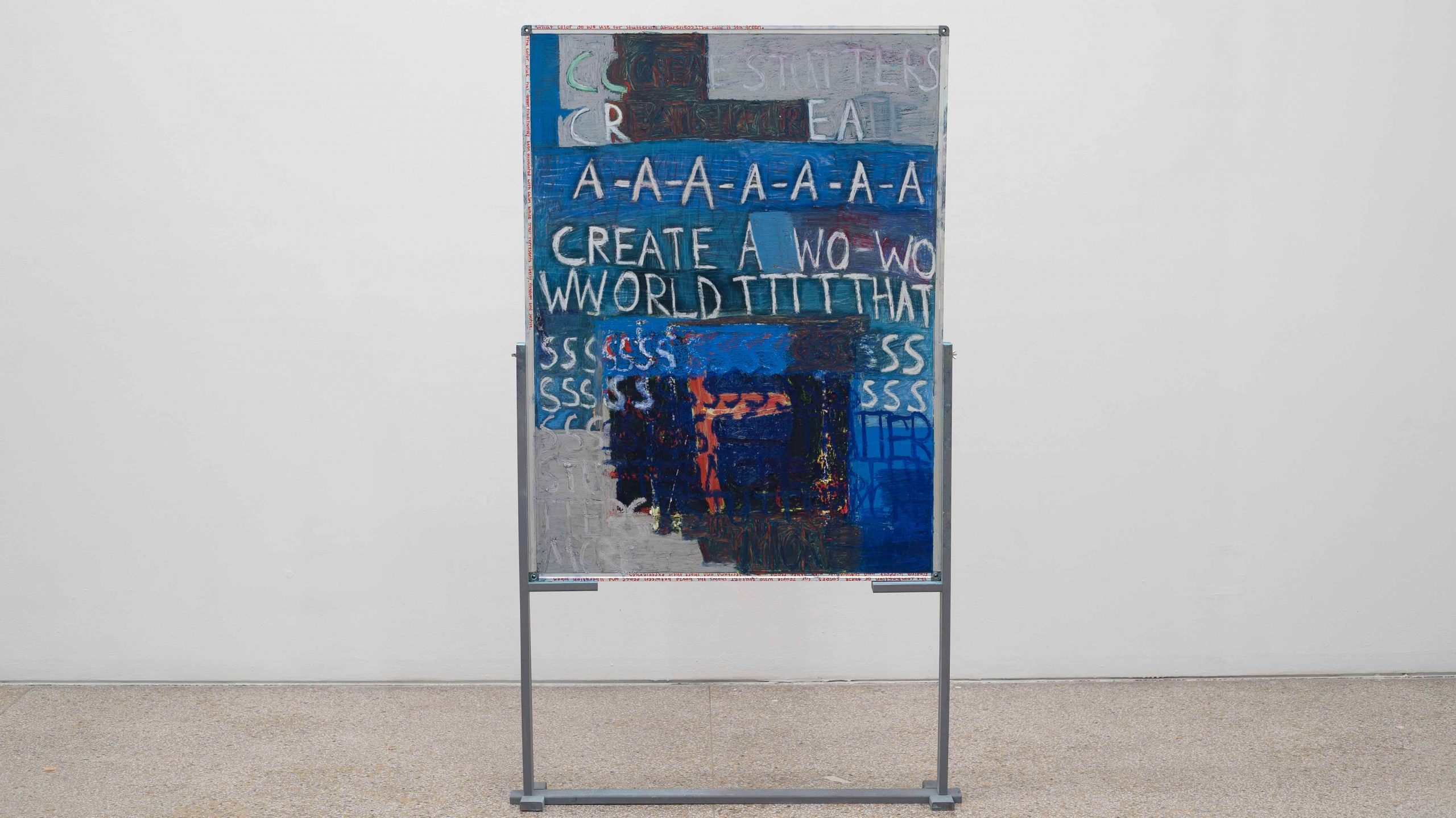

Sometimes I refer to it as my stutter, but sometimes I refer to it as the stutter because to me stuttering is not bound t-t-t-t-t-to my body. It is a phenomenon that occurs between me and whoever I’m speaking to… I like to think of it as something we share.

JJJJJerome Ellis, “Time Bandit,” 2020

The belief that it takes only one person to stutter reinforces an image of people as isolated beings, each waiting for messages to be sent their way. Communication travels one way—from the speaker to the listener (and then back again). Within this model, stuttering is a breakdown that stops the message from arriving. Why is the listener responsible for breakdown if they are just waiting on their end?

Ableist Listening

Yet this viewpoint feels too simple. It also causes harm. When the speaker alone is held responsible for miscommunication, ableist listening is happening. Ableist listening is not, first and foremost, a mean-spirited rejection of disabled voices. It is more mundane: a shared habit of listening, like an unconscious filter that automatically screens out dysfluent speech. Ableist listening assumes that since effortless speech is the norm, effortless hearing is also the norm. Any difficulty of communication lies solely with the speaker. If a listener must concentrate in ways they are unaccustomed to or believe they “didn’t sign up for,” they can blame the speaker and mentally check out or physically leave the conversation. The speaker is then left with stigma, shame, and a sense of needing to “fix” themselves—while the listener can go about their day.

We can understand this more clearly by looking at accents. Imagine you’re in a room where someone with what you would consider a strong accent is speaking. A group of listeners is straining to understand. At that moment, who is really struggling to communicate? Is it the speaker who is “failing” to speak clearly or the listeners who are “failing” to listen? Or imagine the opposite: a room where all but one person is speaking in accented speech. That one person struggles to follow the conversation. In either case, when one group of people is outnumbered—and when one group has more social power—it becomes easy to shift responsibility for “failing” communication onto the minority.

This example illustrates why communication is always shared. If someone speaks but no one is willing to listen, then communication did not actually happen. Both parties contribute to the process. Notice how the words communication and community come from the same root: communis, which means sharing something in common. In any act of communication there is a relation formed. It isn’t a speaker handing over a package to a passive bystander—it’s an active engagement between everyone involved.

The voice, the stutter, only becomes “mine” in the act of sharing and becoming entangled with the world. The voice emerges from the contributions of multiple actors.

Joshua St. Pierre, “Stuttering and Ableism”, 2023

If communication is a way of being together and having something in common, then the idea of isolated beings connected by information doesn’t fit. Humans are inherently social; people begin in one another’s company, like dancers on a shared floor. And like dancers, speakers and listeners share common movement and time, each responding to the other to create something meaningful.

We might compare ableist listening to a rigid set of dance rules that penalize any performer when they go off script. These rules can demand a certain speed, a certain order, or total smoothness. Anything else is a disqualifying error. But like dancing, communication is shaped by the others on the dance floor. If one’s partner slows down or repeats an earlier move, the other must notice and respond:

I am falling through the air for an instant, then catching the ground again, like Fred Astaire pretending to trip when he dances.

Emma Alpern, Why Stutter More?, 2019

When one dancer clings to their premade idea of what a dance should be—rather than responding to the partner and the dance in front of them—the shared rhythm and movement dissolves. The dance ends.

Ableism is a cultural habit that pushes listeners to accept “normal” rules of communication. In this way, it is ableism that fails communication. When listeners expect effortless speech, they bring unspoken assumptions into every conversation that push stuttering out: “Speaking should be easy,” “People should get their words out quickly and without error,” and “If you can’t speak fluently, you’re not worth listening to.” Dysfluent speakers are penalized for failing to meet the expectations of listeners. Ableist listening is not just a refusal to hear; it is a refusal to join the shared making of meaning.

Like dancers on the same floor, speakers and listeners are co-creators of each interaction. A shared moment of stuttering engages the deeper space where meaning genuinely emerges. A shared moment of stuttering is a site to gather and renew the practice of communication: the practice of being responsible to one another as we construct meaning together.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- How does the behaviour of the listener shape the experience of the speaker? What is the role of the listener in communication?

- Does the role of the listener shift at all when the speaker is dysfluent, or should all communication be engaged with in the same way? How can a listener best honour a dysfluent speaker?

- Dysfluency studies suggests that it is the speaker and listener’s shared responsibility to make meaning. How does this challenge the ableist assumption that it is solely the speaker’s responsibility to follow fluency norms and communicate a clear meaning to the listener?

- How does the binary understanding of speaker and listener reduce the potential for meaningful communication?

- How did the use of the listenometer in the New York Times video initially make you feel when it cut out John’s stutters? How did your feelings change when it reveals that the listenometer is a metaphor for the listener, and their patience, eye contact and willingness to listen?