Stuttering New Stories

We are in the midst of a social movement: the rise of stuttering pride. The recent growth of dysfluency-affirming communities has pushed open the door that has kept stuttering closed in a room, away from the larger community (and insights) of disability activism and disability studies. It matters who gets to tell the stories about disability:

Stories about us are boring. As predictable and ubiquitous as they are dangerous, normate narrations of our lives are as straight as they come.

Joshua St. Pierre and Danielle Peers, “Telling Ourselves Sideways, Crooked, and Crip”, 2016

.jpg)

The stories about stuttering have become as predictable as they are dangerous: a personal tragedy to pity; genetic coding gone astray; a neurological flaw in need of correction; a social contagion to avoid; a social obstacle to manage; a test of faith; an opportunity for divine healing; a sign of nervousness. Such stories are driven by ableist stereotypes and assumptions that reveal more about the social perceptions of speech and speech disability than the lived reality of stuttering itself.

Because stories have the power to reshape worlds:

Telling our individual and communal selves otherwise has been a pivotal move for many Mad, Deaf, neurodiverse, disability, sick, and crip activists and communities over the last century.

Joshua St Pierre and Danielle Peers, “Telling Ourselves Sideways, Crooked, and Crip”, 2016

Stuttering has arrived late to this party. It was only in the 2010s that the community wholeheartedly took up the challenge to rewrite the narrative against the biomedical grain. A number of factors account for this historical separation of stuttering from disability studies and the disabled community.

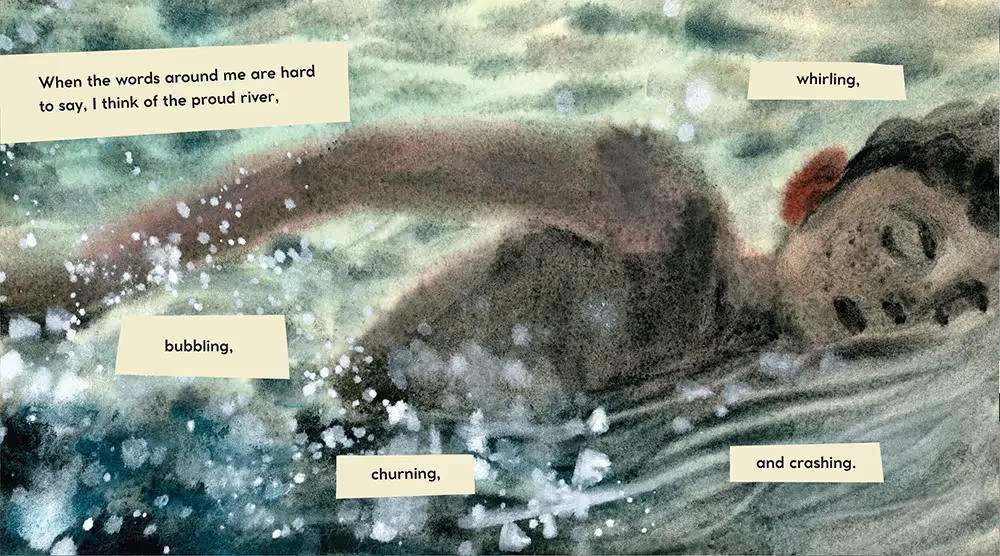

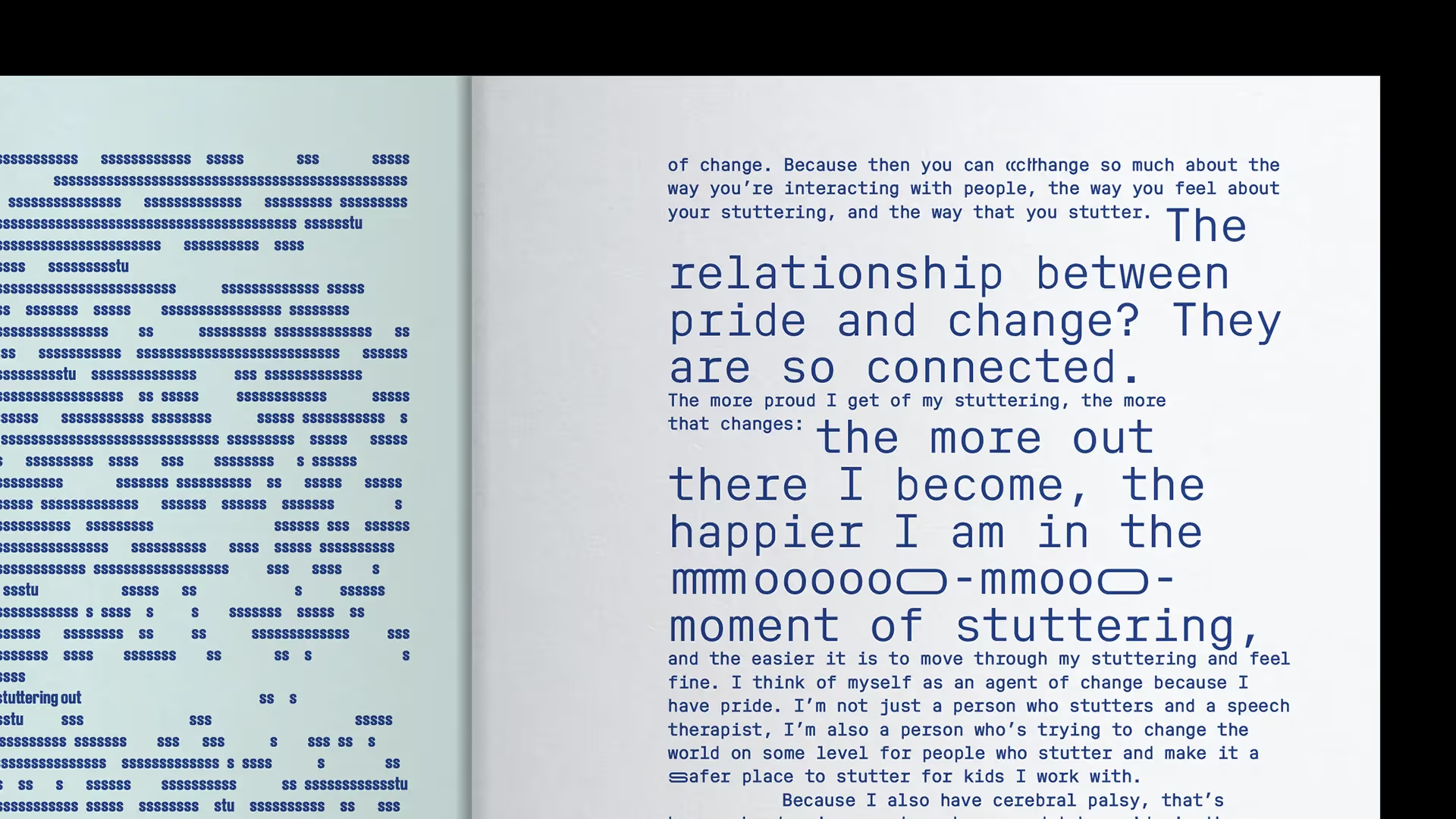

Nevertheless, a collective effort to rewrite the narrative of stuttering is happening, and it has already resulted in both a new social movement—stuttering pride—and a new academic subfield—dysfluency studies. The narrative change is easy to grasp: Dysfluency is not a deviation but an enduring, and even valuable, form of human neurological variation. As with ADHD or autism, stuttering is a type of neurodivergence: a different yet natural way that some brains function.

From out of the community effort to retell its own story, stuttering has emerged as a social identity, a collective banner under which people who stutter can identify proudly and find belonging in community, including the wider disability community. Why, this new community asks, should fluency have anything to do with being heard, respected, accepted, or valued? Why are we collectively attached to the idea that stuttering is something one has, rather than something we share? What can we gain from stuttering? Can we find dysfluent speech valuable? What about beautiful? Can we transform our belonging?

Such questions are powerful; they drive social change. Stuttering art and culture are thriving, as is the grassroots knowledge that dysfluency is not an individual “problem” that can be solved with individualized answers. If stuttering is a problem, it is first and foremost a social one—of how we organize our world to empower “normal” speech but exclude nonnormative speech.

Stuttering pride is thus a community that honors and learns from dysfluency as a valuable form of human difference. Stuttering pride is all too mindful of the longstanding efforts to stamp dysfluency out of society, but also knows that—despite these efforts—dysfluency is a part of human language that isn’t going anywhere. In this way, stuttering pride invites us away from the fountain of cure, the promise of a magical elixir, and calls us instead to listen to human life with greater care.

When a stammerer, like myself, says something seemingly simple and superficial, such as “H-H-Hello, how are y-y-you?”, we still have to fight for it. We have to resist both the physical struggles stammering can bring and the stigma of speaking with a stammer. We have a chance—unavailable to people who are fluent—to physically show that words are worth something. Stammerers can help society to appreciate that all of our interactions have value.

Patrick Campbell, “Stammering as Weight”, 2019

Gathered in the clearing, we can hear at least two refrains of stuttering pride.

Digging out ‘Roots’ of Stuttering Oppression

Stuttering pride is a community oriented around transformative belonging. As such, it seeks to address not merely the symptoms but also the source of stuttering oppression. For example, people who stutter experience stigma that causes a great amount of social and emotional harm. Curative belonging makes individual stutterers responsible for fixing themselves and engaging in “self-talk” if they want to experience less stigma. Inclusive belonging insists the problem of stigma stems from a lack of rights for people who stutter and a lack of education for able-bodied folk about stuttering. Both of these approaches address the symptoms of stuttering stigma and oppression, but not its root cause: ableism and compulsory fluency. Stuttering-pride communities focus attention on the forces that produce vocal injustice in the first place and seek out alliances with other communities affected by vocal injustice in our common pursuit of a more habitable world.

Stuttering Gain

Where the dominant approach to stuttering makes it only a problem and source of suffering, stuttering pride draws from a powerful concept in the Deaf community called “Deaf gain,” the idea that Deafness imparts unique strengths, perspectives, and contributions that would otherwise be lost. One reason we take pride in stuttering is because it adds depth and meaning to our lives and to the world. Chris Constantino gives one example:

Much of human communication is routine and automatic. People speak without actually saying anything, they engage in a ritualized exchange of mundane phrases in a rehearsed rhythm that requires little thought. Speaking is used to keep others at a distance rather than to bring us closer together. […] Luckily for us, stuttering shatters this ritual. The irregular rhythms of our speech allow for open and honest communication unburdened by meaningless, stereotyped phrases. When people speak to us, it breaks them out of their routine. They cannot anticipate our responses.

Chris Constantino, Stutter Naked, 2019

In the clearing, the unpredictability of stuttering is a gain, a force that transforms rigid choreographies of communication into new dance rhythms. As we have suggested throughout this block, stuttering adds much to our lives. Dysfluency is an invitation into such gifts as community, a deeper sense of time, a keen awareness of social dynamics, a dysfluent aesthetic that celebrates rupture of the ordinary, and the beautiful weight of communication. As Patrick Campbell writes:

Maybe we can be seen as orators who bring different attributes to speaking and represent a different set of values. … [O]rators with a different kind of beauty. Ones who help remind society of the weight and effort that lies behind every time we communicate with another.

Patrick Campbell, “Stammering as Weight”, 2019

To be open to stuttering gain is to pursue a different set of values than an ableist society offers. Instead of instant and effortless communication holding our attention, stuttering gain is curious about the value of slowness, of repetition, of interruption, of relationality, of unpredictability, of the weight and wrinkles in speech.

While this may all be true, pride is still complex. Pride about stuttering does not mean embracing “toxic positivity”—pretending that everything about stuttering must always feel good. We know firsthand that stuttering can be challenging and frustrating. It is important to allow room for these fraught feelings. Above all, stuttering pride is never a demand: “You must always feel proud about stuttering!” Stuttering pride is rather an invitation to engage honestly with the full complexity of stuttering: its challenges, its oppression, and its power.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- How have dominant stories about stuttering been “predictable and dangerous”? What new stories or narratives are emerging in stuttering pride, and what do these new narratives achieve?

- Have you personally experienced stuttering gain? How does the language of gain challenge dominant understandings of stuttering?

- What kinds of care, support, or community might replace the cure-focused model? How can we work to implement these in everyday life?

- How can we use art and culture to shift the narratives around stuttering?

- Beyond stutterers, who else experiences vocal injustice? How can the stuttering community both support and be supported by wider communities that experience vocal injustice?