Introduction

Belonging is a basic human need, and it prompts fundamental questions for people who stutter: Do we have a meaningful place in the world? Are we wanted? What are we wanted for? When the force of compulsory fluency is strong in a society and ableist listening is dominant, people who stutter find themselves excluded. We become strangers even to our own voices. And yet a desire to belong endures within the stuttering community. We want to share a common world. We want community. The disagreement lies in what belonging means and how to achieve it. This section offers a framework to understand and start to navigate these differences.

Curative Belonging

Curative Belonging is currently the dominant approach. This is the belief that people who stutter can belong if they first become fluent. Here, only normal people can expect a seat somewhere at the kitchen (or boardroom) table. Disability is a danger, something that weakens the individual and the group. According to this way of thinking, disability erodes what makes us human—for example, the ability to be ourselves and gather with others. If stuttering is what impedes belonging, it follows that we should try to remove stuttering. Gene therapy, anti-stuttering pharmaceuticals, and fluency shaping are, in this way, often well-intentioned attempts to foster belonging by eliminating dysfluency.

However, if the culprit is not stuttering but ableism, then aiming at fluency misses the mark. The notion that “if you talk like a normal human, then you can expect to be treated like one” reinforces the wrong idea. If fluency has become a gateway to belonging, our goal should be to dismantle that gate, not move toward it.

Inclusive Belonging

Inclusive Belonging takes a small yet significant step away from compulsory fluency. Inclusive belonging is the belief that people who stutter can belong to the degree that they can be inserted into an existing world—without altering or breaking it. At the table of inclusive belonging, stuttering is not welcomed with open arms, but it is at least tolerated when made palatable. Easy stuttering, “good communication,” and disclosures designed to put people at ease may be part of this approach.

All voices, goes the official story of inclusion, are invited to the table. This is a major departure from curative belonging, and it is important to appreciate the hard-fought struggle by disability communities to have baseline rights, acceptance within society, and employment opportunities. Inclusive belonging has been good news for the stuttering community.

Yet in practice, not everyone has time to speak at the table of inclusion, let alone be heard, trusted, and welcomed. And for people who can be heard, only parts of who they are can be included in the conversation. Inclusive belonging, then, is fractured: A person belongs, and can thus be excluded, in part and pieces. Complex parts of our stories, such as the entanglement of ableism with poverty or racism, must be left behind. Likewise, “normal” parts of dysfluency can be included at the table of inclusion, but the weird and disruptive parts necessarily fall to the floor. Polite and apologetic stuttering has a place, but not the unapologetic and ugly.

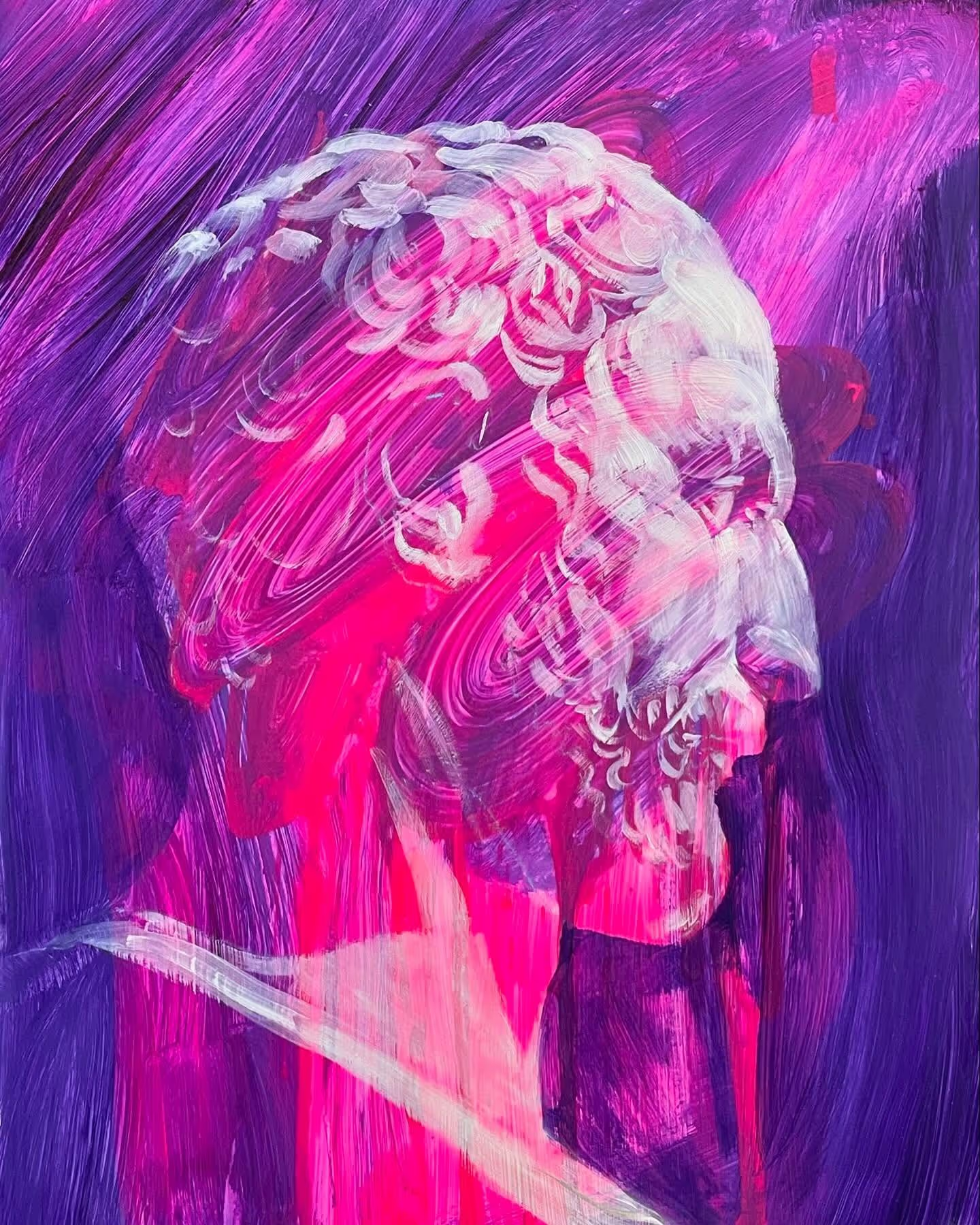

Stutterers experience a uniquely embodied and passionate version of speech, but we are not usually equipped to observe it with curiosity. Rather, when we seek help, we are given ways to tamp down the strangeness of stuttering.

Emma Alpern, Why Stutter More?, 2019

In the logic of inclusion, society can tolerate stuttering as long as it remains respectable, with its surprising edges sanded down. This makes inclusive belonging conditional, like a membership that can be revoked at any time. “You’re allowed in, just don’t disrupt the party.” To belong at the table of inclusion, stutterers must remove friction: We tame, explain away, and/or apologize for our speech, clinging to what bits of normalcy stuttering can manage.

While inclusion offers a fragile kind of belonging, it also remains a meaningful refuge for many in the stuttering community. This refuge exists within a larger world that, at this time, offers little welcome to dysfluent life.

Transformative Belonging

Transformative Belonging makes a departure from both curative and inclusive belonging. In this mode, stutterers seek a meaningful place in the world not despite their dysfluency but because of it. As disability justice writer Mia Mingus writes, “I don’t just want us to get a seat at someone else’s table, I want us to be able to build something more magnificent than a table, together with our accomplices.” Here, we belong through the collective act of remaking the table as a site of gathering and sharing. Transformative belonging takes root in the act of building something new together. In other words, if cure and inclusion declare “these are the basic terms of belonging—take them or leave them,” transformative belonging grows in the possibilities of remaking when, why, where, how, and what it means to belong.

To invest so much time and effort into correcting a body is to give up a greater and more profound opportunity: to redesign society to make stuttering fit easier into the spoken fabric.

Zahari Richter, “On Stuttering Activism and Resistance”, 2019

Instead of contorting ourselves to fit in the fluent world, how can we inhabit our stutter and also make the world stutter? The disability writer Eli Clare desires that we “create the space to make our bodies home, filling our skin to its very edges.” We likewise want to grow to a place where we can inhabit our stuttering, fill it to its very edges, and make a place for it. In a world that demands everyone speak smoothly, finding a way to belong with our own stuttering voices—and on their own dysfluent terms—is a radical act. It is also a collective act that aims to shift the place of dysfluency in our society.

To be at home in dysfluent bodies requires that we begin to make a habitable world for dysfluency. Dysfluency requires community to flourish.

Joshua St Pierre, “Misfits in Meaning”, 2019”

Making a habitable world for stuttering means harnessing two kinds of friction: a “fierce no” and a “fabulous yes.” The former rejects ableist values, while the latter creates dysfluency-affirming values.

In the first instance, transformative belonging is created in the collective struggle of the “fierce no”: challenging what it means to belong in an ableist world by calling out prejudice, making waves, and dismantling fluency privilege. This is important work being done by the stuttering community.

At the same time, the rise of stuttering culture and art signals a “fabulous yes” that engages the beauty and power of dysfluent speech. Transformative belonging affirms dysfluent forms of life on their own terms and welcomes others into belonging on these terms. In a 2025 exhibit, artists Conor Foran and Paul Aston pose a provocative question to a fluent society: “Wouldn’t you rather talk like us?” This is an invitation to explore belonging from an entirely different starting place.

Both a “fierce no” and a “fabulous yes” need each other. Any community focused exclusively on rejecting harmful values will become rigid and reactive. Yet without this rejection, affirming the power of dysfluency becomes powerless. Dysfluent life cannot flourish unless we find cracks in compulsory fluency and loosen its hardened ground.

We in Stuttering Commons seek transformative belonging and strive toward a social world that genuinely welcomes dysfluency and helps it thrive. However, these modes of belonging tell a more complex story than a straight line from “bad” (curative) to “better” (inclusive) and “best” (transformative). Voices that are excluded and shamed by a larger society find shelter in being normal—in not being a spectacle for once. In an ableist world, speaking more fluently or just being included means safety; it is a survival tactic. Belonging, by definition, involves more than survival, but finding belonging is never straightforward (especially for people who experience multiple forms of oppression). Belonging always takes some experimentation. In particular, disabled people often find themselves moving between sites of inclusive belonging and those that offer transformative belonging.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- In what ways does “inclusion” demand stutterers conform to the norms of fluency, and what are the limitations to this kind of belonging?

- What are some examples (real or hypothetical) of “fierce no” and “fabulous yes” for the stuttering community?

- How do the three modes of belonging in stuttering parallel similar shifts in other disability or social justice movements? How can dysfluency learn from these similar movements?

- In your daily life, where do you see more curative, inclusive, or transformative attitudes toward differences?

- How does the concept of “transformative belonging” help us think about community differently?